China Sees Itself at Center of New Asian Order

![]()

HORGOS, China—In a valley flanked by snow-capped peaks on China’s border with Kazakhstan, a vision of Beijing’s ambitions to redraw the geopolitical map of Asia is taking shape. This remote outpost, once a transit point for Silk Road merchants, is where China is building one of its newest cities.

Covering more than twice the area of New York City, Horgos had just 85,000 residents when it was founded in September, enveloping several towns and villages in an area known for lavender fields.

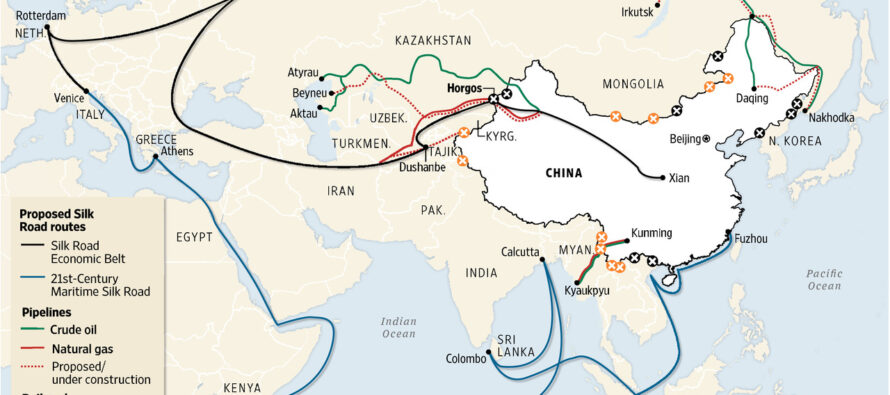

China’s plan is to transform the sleepy frontier crossing into an international railway, energy and logistics hub for a “Silk Road Economic Belt” unveiled by President Xi Jinping last year to establish new trade and transport links between China, Central Asia and Europe.

President Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping arrive for the APEC Summit family photo in Beijing on Monday. REUTERS

Horgos is a small element of China’s wider effort to bind surrounding regions more closely to it through pipelines, roads, railways and ports, say diplomats and analysts who have studied the plans it has made public.

The plans also include an Asian-Pacific free-trade deal, a $50 billion Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and a $40 billion Silk Road Fund that Mr. Xi announced last week, promising aid aswell as investment from Chinese private and state firms.

In a speech to business executives Sunday, he said China’s plans would boost growth and improve infrastructure across the region to help fulfill an “Asia-Pacific dream,” echoing his domestic political slogan of a “Chinese Dream” to rejuvenate the nation. “With the rise of its overall national strength,” he said, “China has the capability and the will to provide more public goods to the Asia-Pacific and the whole world.”

The push is a counterpoint to China’s recent military assertiveness, which has antagonized many neighbors and prompted the U.S. to launch its “pivot to Asia” strategy of focusing more military and other assets on the region. Beijing is now trying to convince countries in Asia and beyond that it is in their interests to accept China as the alpha power in the continent.

A woman receives goods for her shop on Kazakhstan’s side of the free-trade zone that the country shares with Horgos, China. TIM FRANCO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

China’s road map for a reconfigured Asian order, centered on Beijing and underpinned by new infrastructure, forms the backdrop to a summit of leaders, including U.S. President Barack Obama , that takes place Tuesday at a specially constructed lakeside complex outside Beijing. Mr. Obama arrived in Beijing on Monday.

The annual Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit, being held in Beijing for the first time, will focus as usual on trade and investment among its 21 members and is set to endorse for the first time a “blueprint on regional connectivity” over the next decade.

But this year, the APEC summit is also about the symbolism of President Xi’s playing host to regional leaders at a time when Beijing is trying to claim a place as Asia’s dominant economic and military power. Mr. Xi also met leaders of Pakistan, Myanmar and five other non-APEC Asian nations Saturday to discuss infrastructure.

“China in a leadership role? That’s not a small message,” Robert Wang, the U.S. senior official for APEC at the State Department, told reporters recently. For China, “It’s pride. We’ve arrived. That has a message. Next time you deal with them, you remember it.”

Some foreign and Chinese scholars, including Zhai Kun, a Peking University international-relations professor, liken China’s push to the U.S. Marshall Plan that helped rebuild Europe after 1945. Others compare it to the tributary system through which China dominated East Asia for much of the last two millennia.

Chinese government representatives didn’t respond to inquiries for this story. Mr. Xi last week said the new infrastructure bank and Silk Road Fund would “complement, not substitute” existing lending institutions.

A Chinese customs checkpoint inspects trucks at China’s border with Kazakhstan in the city of Horgos, to which China has built a new…

Still, the plans have stirred debate among Western and Asian governments, with some welcoming China’s development drive and others wary of its strategic designs.

Some Western officials also worry a flood of Chinese development money will undermine governance standards at existing lending institutions like the World Bank, especially if China channels funds to its own companies, to politically motivated projects or to environmentally damaging ones.

In the run-up to the APEC summit, people familiar with the matter say, the U.S. blocked China’s efforts to begin negotiations on a regional free-trade agreement, the Free Trade Area of the Asia Pacific, because it conflicted with a Washington-backed alternative known as the Trans-Pacific Partnership that excludes China. Beijing continued to promote its preferred deal in presummit meetings but won endorsement for the pact only as a long-term goal.

The U.S. also lobbied against some large economies joining the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which was established in October by China and 20 other nations as an alternative to the World Bank—dominated by the U.S.—and the Asian Development Bank, led by Japan.

Secretary of State John Kerry at a news conference in Beijing on Saturday said the U.S. was a Pacific nation that took its regional interests and responsibilities seriously. He also urged countries in the region to establish rules and norms through multilateral institutions “where all voices can be heard.”

A State Department representative said the U.S. saw China’s Silk Road plans as “complementary to U.S. efforts to promote economic connectivity” but considered it critical that any new international financing bodies upheld existing ones’ standards on governance, environmental and social safeguards, procurement and debt sustainability.

China has long sought to extend its influence in Asia through aid and investment, and to gain access to Central Asian energy resources. Some efforts now under way are rebranded versions of earlier projects.

But the push has expanded and taken on greater urgency under Mr. Xi, who has articulated a more expansive role for China in the world than his predecessor did. In speeches over the past year or so, he has laid out a vision that combines continuing infrastructure projects with ambitious new ones that together could tally tens of billions of dollars of spending.

Mr. Xi proposed the Silk Road Economic Belt, one of the effort’s pillars, on a Central Asia visit in September 2013. He called for building a transport corridor connecting the Pacific Ocean to the Baltic Sea and linking East Asia to South Asia and the Middle East to serve a combined market of some three billion people.

On that trip, he oversaw the signing of deals valued at $30 billion in Kazakhstan, including oil and gas projects, and agreed to pump $3 billion into loans and infrastructure in Kyrgyzstan.

During a trip in Indonesia the following month, he put forward another pillar, a maritime trade corridor he called the 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road. It entails building or expanding ports and industrial parks across Southeast Asia and in places including Sri Lanka, Kenya and Greece, along with a goal of expanding bilateral trade with Southeast Asia to $1 trillion by 2020—more than double its level last year.

He invoked the spirit of Zheng He, a Chinese eunuch admiral who sailed a fleet of treasure ships to Africa in the 15th century and is celebrated as the face of an era of Chinese maritime power.

In May, Mr. Xi was more explicit about his goals in a speech dedicated to a “new Asian security concept” at a Shanghai summit of regional leaders.

“It is for the people of Asia to run the affairs of Asia, solve the problems of Asia and uphold the security of Asia,” he said, calling on Asian countries to “advance the process of common development and regional integration.”

Although Mr. Xi didn’t mention the U.S. by name, many Chinese and Western analysts agree his appeal sent a message to Washington that it should accept a lesser role in the region, which, according to the Asian Development Bank, requires infrastructure investment of $8 trillion by 2020.

“He’s taking these concepts that have been around forever,” says Chris Johnson, a former CIA China analyst now at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, “and then actually doing it, putting the bones on it, putting the money behind it and frankly telling everybody in the system, ‘I’m serious about this.’ ”

Mr. Xi’s plans appear to reflect a worldview in which China increasingly sides with developing powers, he says, rather than working alongside the U.S. within the existing Western-dominated international order.

It is far from clear whether all the intended recipients of Chinese largess will embrace the offers. Past Chinese projects have run into trouble in Myanmar, including a $3.6 billion dam that was suspended in 2011, while a proposed rail link to Pakistan has been held up by political uncertainties.

But some individual projects appear to be gaining momentum and new financing sources, including a $100 billion development bank that the so-called Brics nations—Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa—agreed in July to establish with headquarters in Shanghai.

In Kuantan, Malaysia, a state-run Chinese company last year began jointly developing a deep-water container port and industrial park and this year agreed through a subsidiary to invest $1 billion in a steel plant there, a project both countries portray as part of the new maritime Silk Road.

On a tour of South Asia in September, President Xi inaugurated construction of a $1.4 billion Chinese-funded port city in Colombo, Sri Lanka’s capital. That month he oversaw the start of construction on a new section of a Chinese-financed gas pipeline through Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. On Monday, China and South Korea are expected to announce a free trade deal—one of several bilateral trade pacts that Beijing is negotiating in the region.

China’s initiatives don’t imply a letup in China’s efforts to assert territorial claims. But China is working harder to present itself as a development ally at a time when some Asian nations wonder about Washington’s wherewithal to underwrite infrastructure projects and military security.

In 2011, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton proposed a “New Silk Road Initiative” designed to improve Afghanistan’s transport links with Central and South Asia, but U.S. officials say progress has been slow.

A vehicle transports passengers around the free-trade zone in Horgos. TIM FRANCO FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

China, by contrast, has the resources and political will to back up its plans, Chinese experts say.“For China, it’s a top-level issue—all government departments are focused on this,” says Peking University’s Mr. Zhai. “Also, President Xi has 10 years to promote this, whereas Clinton only had two or three.”

The scale of China’s ambitions is evident in Horgos. For years, the border here was closed due to China-Soviet tensions. Although the border reopened in 1983, trade was negligible until recently because of continuing tensions and poor transport links.

That has changed over the past few years. First came a gas pipeline from Turkmenistan that enters China in Horgos. Then China built an expressway to the border here. In 2012, a cross-border railway link was completed, and a free-trade zone spanning the frontier was established.

China upgraded Horgos to a city in September, giving the local government greater powers to develop land. Official maps and statements now describe Horgos as China’s main land port on the Silk Road Economic Belt.

The upgrade expanded Horgos’s surface area by almost 100 times, says Wu Hao, deputy director of the Horgos free-trade zone. He says more than 20 billion yuan ($3.25 billion) has been invested in the Chinese side of the trade zone, which features five multistory wholesale markets where Kazakh traders buy Chinese tires, furs, electronics and other consumer goods. A luxury hotel and an exhibition center are being built and will be ready by 2017, says Mr. Wu. There are also new warehouses, villa complexes and industrial zones, a fast-track border crossing for large trucks and a new railway station.

The Kazakh side of the free-trade zone has lagged behind, with only a small cluster of cargo containers and tents selling Russian chocolates and other comestibles. Kazakh traders complain that Almaty, the nearest Kazakh city, is a bumpy five hours away.

Kazakh officials say they will start building malls and hotels and finish upgrading the road to Almaty next year. That is one of the last sections of a highway from China’s east-coast port of Lianyungang to Russia’s St. Petersburg, to be opened by 2016.

Trains are already taking cargo from China via Horgos through Kazakhstan and Russia to Duisburg, a German port. It takes about 15 days, compared with about 40 by ship. In September, a shipment of automobiles from Europe entered China by rail for the first time.

Zhang Jian began selling vegetables on the street in Yining, about 60 miles from Horgos, in 1983. Today, he owns a company he says exported $60 million of fruit and vegetables to Central Asia last year.

He plans to build a packaging-and-processing facility next year to export produce through Kazakhstan to Russia, where demand is up, he says, because of sanctions over the Ukraine crisis.

“Horgos used to be a small town with a very low profile,” he says as workers load one of his trucks with garlic to be shipped over the border. “Now it’s changed to a city, its reputation will grow much bigger.”

—Bob Davis, Lilian Lin, Kersten Zhang and Yang Jie contributed to this article.

Write to Jeremy Page at jeremy.page@wsj.com

selected and reviewed by Maurizio Leonelli and Guglielmo Guglielmi

Related Articles

UNGASS 2016: cosa c’è in gioco? Intervista a Peter Sarosi

![]()

UNGASS 2016 non sarà un punto di svolta, dice il direttore direttore di Rights Reporter Foundation, Peter Sarosi, a Global Rights. «Ma è vero che la società civile è più forte e questo è positivo. La riforma non verrà dall’ONU, la riforma è guidata dalle politiche locali e nazionali»

UNITED NATIONS INDICTS TURKEY FOR “SERIOUS RIGHTS VIOLATIONS” in NORTHERN KURDISTAN

![]()

March 10 2017: The UN’s human rights office today released its report accusing Turkey of serious human rights violations.

Erdoğan Prepping New War Pitched as an Anti-PKK Operation

![]()

Turkey’s military and Prime Minister have announced a new illegal ground campaign said to be an ‘anti-PKK operation’ in Iraq